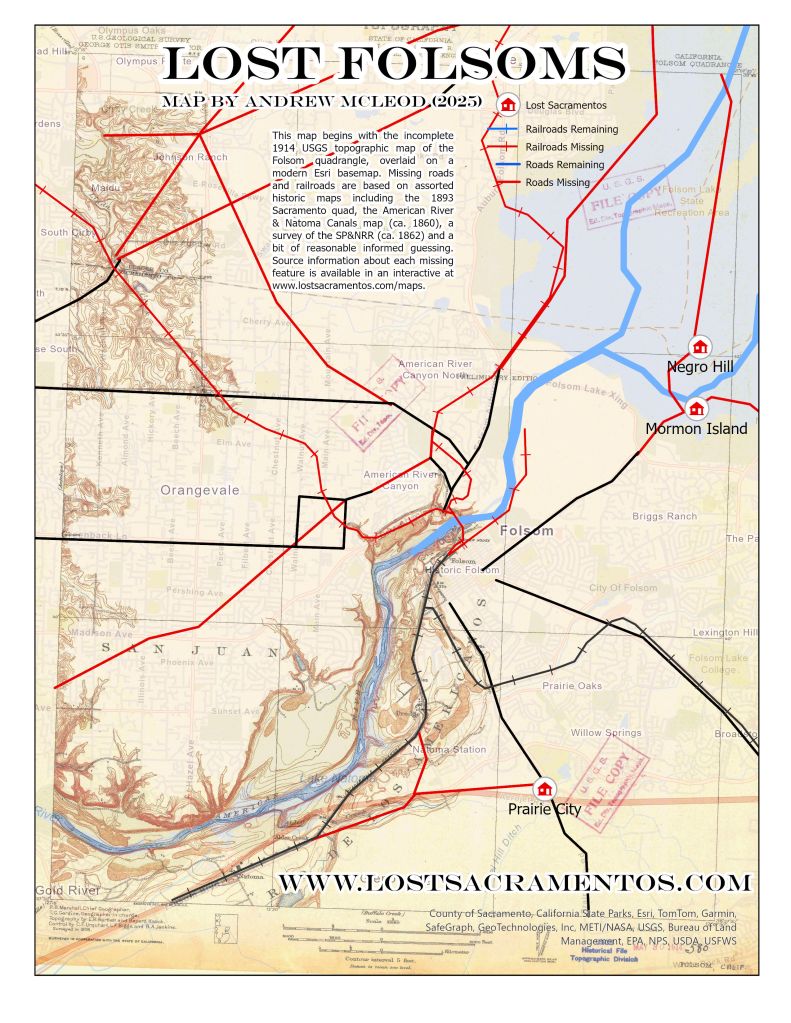

The Lost Folsoms bibliographic map is below.

Digitized Historic Maps:

Lost Sacramentos are often hiding in plain sight, in a growing collection of digitized primary sources that are now freely available online. Thanks to all the archivists who have done the sometimes tedious detail work to get these materials uploaded!

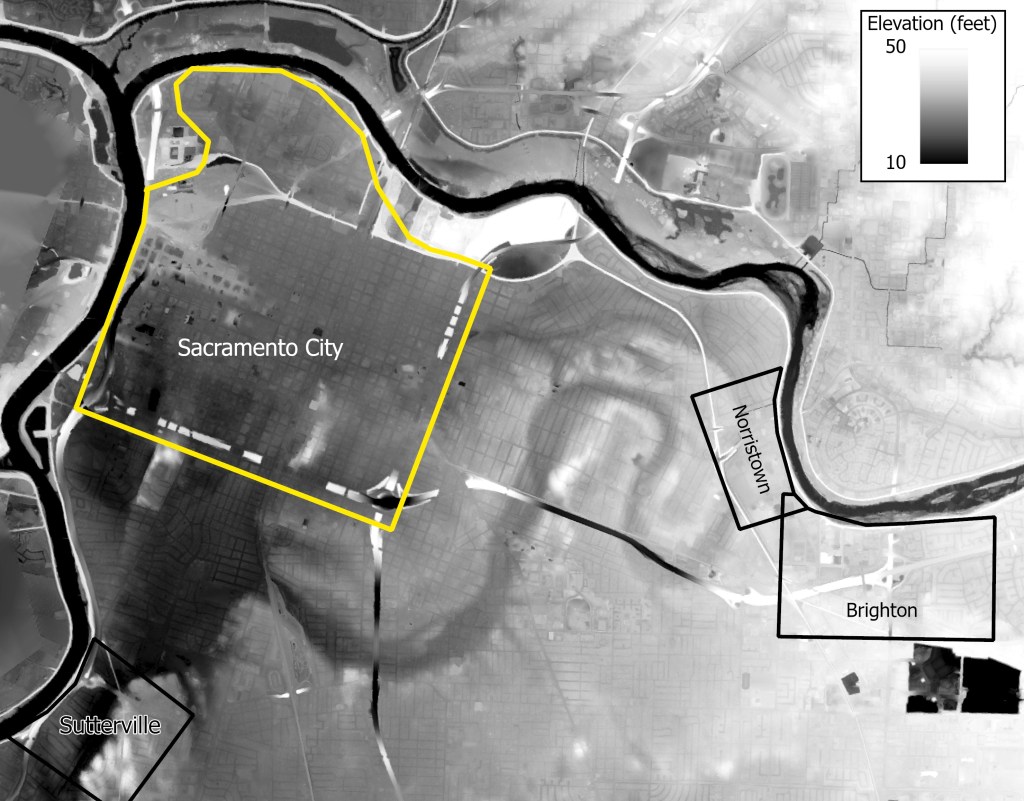

The Sacramento City vicinity was home to numerous false starts and disappearances, which were brilliantly displayed in 1913 cartography by Phinney, Cate & Marshall. While slick and professional at first glance, this deeply subversive map depicts what was lost, including vanished towns, failed subdivisions and wandering thoroughfares. Unfortunately, Brighton is just off-frame, while both Boston (upstream of Old Sacramento) and the old Sutterville-Brighton Road are not depicted. This map raises as many questions as it answers.

Despite low resolution of this scan, Theodore Judah’s vision for the Sacramento Valley Railroad reveals the prominence of the vanished upland towns of Prairie City, Mormon Island and Negro Hill, as well as the Sutterville-Brighton Road that once bypassed Sacramento City and the hilly tangle of sloughs now known as East Sacramento. It also notably shows the railroad’s destination as “Negro Bar” (which was overrun by Folsom in another Judah map). While this version is unfortunately low resolution, a hard copy of the original is available through the California State Archives.

But by 1865, something had gone haywire. A recorded map of the Liedesdorff rancho now shows its entire northeastern section blanked out by the “Natoma Purchase,” which appears to obscure the Sacramento Valley Railroad and Folsom (which nonetheless survived), as well as the Coloma Road and Prairie City (which did not). Despite two major streams heading toward the mines (Alder and Willow Creeks), this attractive landscape is depicted as a void with none of the normal subdivision then underway just downstream.

Folsom is an area of particular interest, with numerous signs of disturbance. The following new map shows a missing transportation system, centered around the Sacramento Valley Railroad shops complex – which employed 1500 people and served no fewer than five railroads in the early 1860s. The creation of Folsom Lake certainly helps explain some disruptions, but other disappearances are more puzzling. Most notably, the lack of connection to Roseville seems connected to other lost routes to Auburn, which appear to have been severed at the county line. In any case, a large swath of land was apparently unmappable as late as 1914, suggesting that the USGS could not decide how to handle whatever traces remained from the previous network of roads and rail. More information about the routes shown herein is available in this bibliographic map.

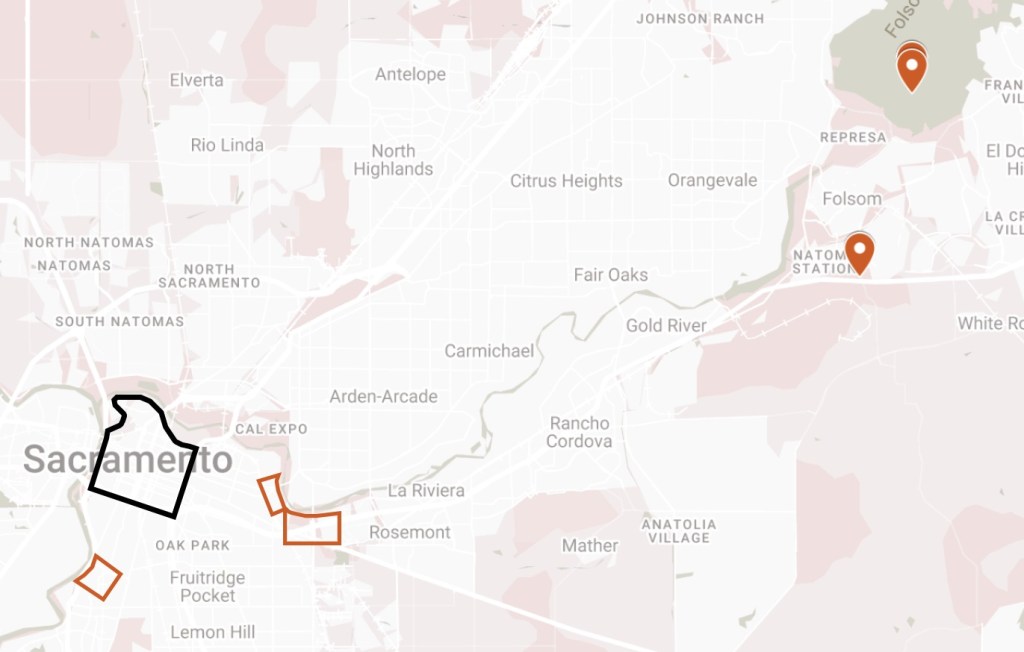

This 1857 map of Rutte, Muldrow and Smith’s Gardens show a pair of vanished crossings towards the current location of Cal Expo (and Auburn) and Del Paso Boulevard (and Marysville). While easy to miss, the river road connecting upstream to Norristown and Brighton proceeds southeastward.

No Norristown maps are yet known to survive, but an 1853 depiction of its successor town shows that this was a stable settlement for at least a few years, with persistent development on at least two blocks. While Hoboken is usually recalled as a fleeting tent city that faded as soon as the waters dropped, several permanent buildings line the Norristown side of a great wedge-shaped commons that once occupied a swath of the modern Sac State campus.

In contrast, Brighton was precisely surveyed and mapped in 1850, and recorded with the county the following year despite significant turmoil in the area. The subdivision’s 320-foot blocks and 80-foot streets would mesh perfectly with the one-mile squares of the Public Land Survey System, suggesting that this was envisioned as a settlement on “government land,”

Maps Produced for Lost Gold Rush Towns of Sacramento.